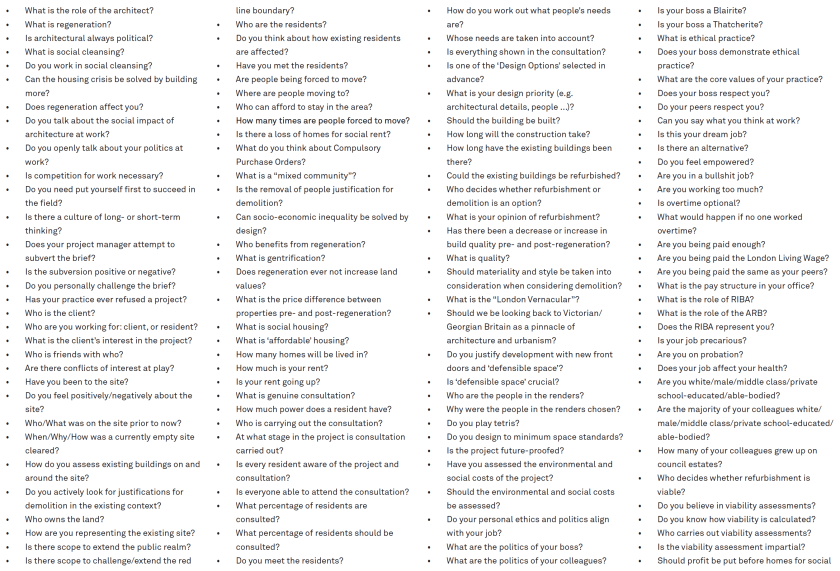

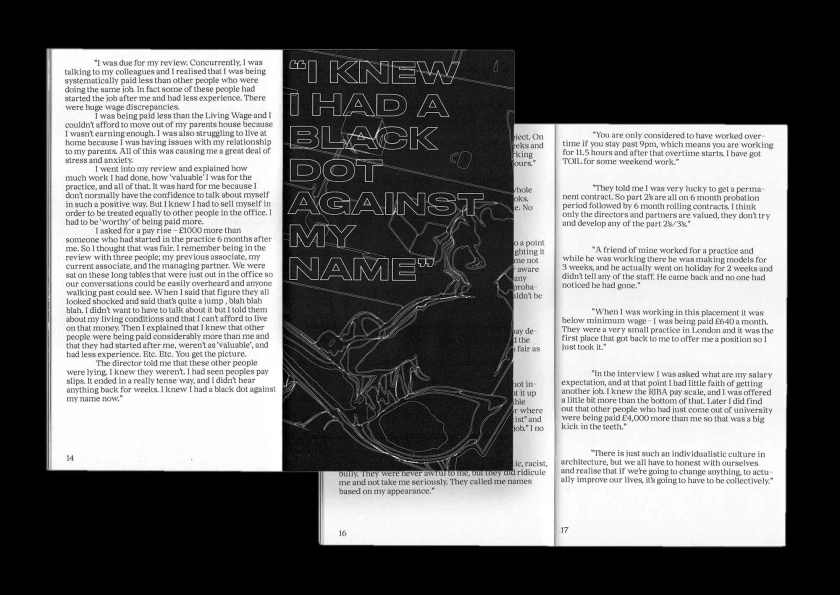

Inequality in architecture plays out differently for individual students and workers across academic institutions and architectural practices. A major inequality, not regularly discussed within discourse on precarious work in architecture, is the discrimination in pay, hiring practices and working conditions dependent on residency status and ‘primary’ spoken language of a student or worker. ‘International’ status also intersects with aspects of class, racial identity; and experiences of architectural students and workers residing in the UK without citizenship are diverse. This post is in response to a number of conversations and interviews with architectural workers in the UK, who are either studying at university on inflated, ‘international’ fees, applying for visa-sponsored work, or currently working on a Tier 2 visa. We refer to ‘international’ students, graduates and workers in this article: an often-used term for people who do not have UK/EU citizenship rights.

“[At UCL] new regulations require international students on Tier 4 visas to physically sign in every month… far exceeding the Home Office’s requirements” © UCL Stop Policing International Students

‘International’ students are an important part of the equation of the ongoing privatisation of higher education. Less regulation enables and encourages institutions to charge higher tuition fee rates dependent on nationality, with some ‘international’ students paying as much as three times (£28,000 per annum) as much as their UK and EU ‘national’ student peers.[1] Higher fees facilitate the offsetting of Central Government grant funding cuts, but also offer new opportunities for ‘growth’. Universities are at the ‘frontier’ of educational imperialism, with many British universities planning to build new campuses across the Middle-East and Asia, opening up new markets for educational products. Beyond being seen as an untapped resource, what treatment do ‘international’ students and workers face, within the university and beyond? This post looks at the treatment of ‘international’ students/workers, and the systemic violence enacted upon them predicated on their residency status, nationality and primary spoken language. Like all migration policies, whilst all non-UK and EU students and workers are seen as ‘international’, and subject to the same instruments of law or financial penalties, whiteness and economic status intersect with an individual’s experience of these borders of labour, education and residency.

“Yes, I couldn’t [take a break]. I don’t know, some students had a break. But I think most students who could have a break in the summer [holidays] were EU students because they don’t care about getting a visa.”

Two-tier

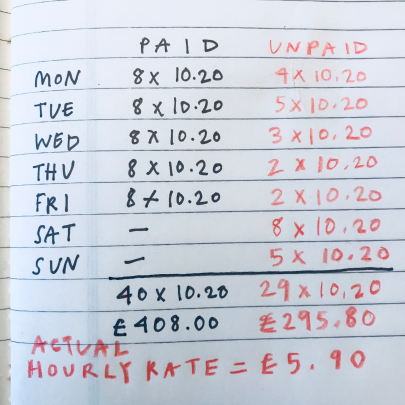

The precarity faced by the ‘international’ stands in contrast to those with secure work permits and lower student fees. In education and employment, there is a two-tier system – in comparison to those with UK and EU citizenship, ‘international’ students and workers are subject to hostile environments, the costs of applying for work visas, higher student fees, restricted choice of landlords, potential bullying from tutors and colleagues, greater pressure to find employment sooner. If you’re an ‘international’ student and you wish to continue to live and work in the UK, you have to apply for a Tier 2 or Tier 5 Visa.[2] The strict conditions of the visa, at risk of deportation, encourage students to take un- or low-paid positions – either just after graduating or throughout their studies – to greater increase their chances of success for sponsored employment. After the grueling test of final examinations, after intense years of study, the clock is ticking – after the 2-year post-study work visa was scrapped in 2012, now graduates have 4 months to secure employment with a starting salary of at least £20,800. Unlike their UK and EU ‘national’ peers, there is no time to rest or take a summer break, no ability to take part-time casual work while looking for the ideal position, nor the power to refuse an offer of work in unfair conditions.

Ahmed Sedeeq, a Sheffield PhD student who spent last Christmas in Morton Hall detention centre for accidentally overstaying a visa, is facing deportation once more.

Ahmed Sedeeq, a Sheffield PhD student who spent last Christmas in Morton Hall detention centre for accidentally overstaying a visa, is facing deportation once more.

Bordered Pressure

“…I was really anxious because it’s completely unclear what my future was. The only thing I’m sure is, I have to go out [of the country] unless I find a job before October. So time was going so fast…. it really is frustrating. Last summer when I was waiting for the jobs I had applied to to get back to me and I felt like my time was really running out. I felt really really frustrated. I almost thought that I needed to leave the U.K. and go back to [Country] and find a job.”

Graduation for many students can be a time of anxiety: the time to put newly-earned academic qualifications into a competitive job-market. Most graduates have a fear of unemployment and rejection, but for ‘international’ students there is the added threat of deportation. The inherent uncertainty of the application process was amplified for this interviewee, the effort channeled into cover letters, portfolio and interview with insecure return.

“Actually, the first time I had an interview with a practice, I thought that the important thing is how well I can explain my work, and that I did a good job studying….What they’re [really] looking for is not about the work being amazing but they’re looking for how a candidate actually communicates their ideas and whether they ‘look’ professional…”

Once the interview appointment is made, there are additional hurdles presented, with face-to-face communication a ground for judgment made on aspects such as racial identity and accent. Racialization influences an employer’s perception about a candidate’s ability, character, or demeanor; often amplifying the expectations employers have of harder-working ‘internationals’. Workers of Asian heritage are perceived to be happy to take on long hours for less pay than their non-visaed counterparts. Once employed, characterization and projection negatively impacts an employee’s experience and ability to progress within the profession.

“I wrote a cover letter about my history and my interest and skills…. I updated my CV and added a couple more pages of my professional work. Then, combining them all together and sending them by email. A day after, the human resource person emailed me about my working visa. ‘Do you have any right to work in the U.K.?” or something like that…. After I got that email I sent them my work placement letter from University…. they asked me how much time I wanted to work at their practice. So I wrote back like ‘I’m looking for a permanent position’.”

The ‘international’ interviewee’s personal merits or academic qualifications are always preceded by their residency status; measured against an economic calculus to maximise profit. For a practice to be licensed to sponsor an ‘international’ student costs between £536 and £1,476 per annum. The price of the visa itself, depending upon whether it’s a transfer or a new application, is between £610 to £1,314 per annum.[3] The conversation about whether someone has the right to work in the UK is one about the monetary cost of, at most, £3,000. The ‘financial risk’ is usually absorbed by docked wages of the worker – meaning very little risk at all to the potential employer.

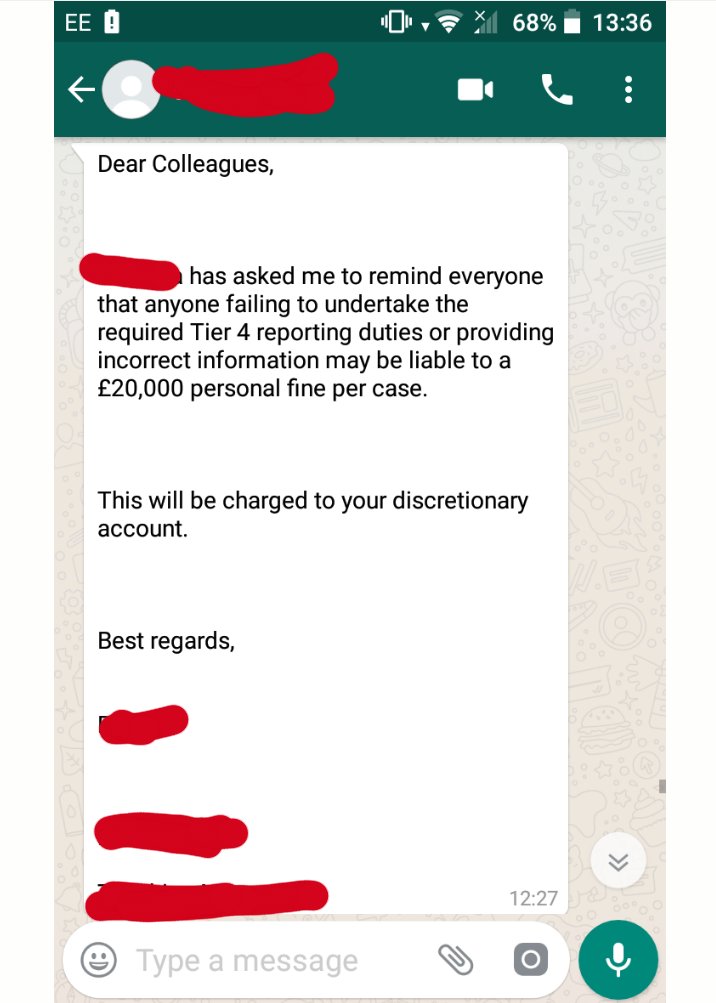

An email sent to lecturers at University College London (UCL) stating that if they fail to comply with the Hostile Environment they may be liable to be personally fined £20,000. Image: Uni’s Resist Borders

An email sent to lecturers at University College London (UCL) stating that if they fail to comply with the Hostile Environment they may be liable to be personally fined £20,000. Image: Uni’s Resist Borders

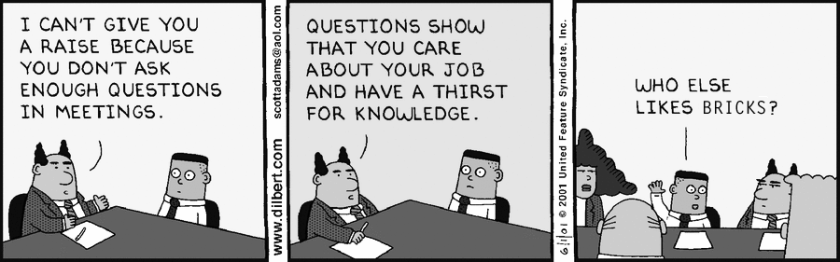

“[Being born outside of the EU without a residency permit] It also affects the interview process. For example, when they interview U.K. or EU students, maybe the interview is more casual, just like a conversation or a casual chat or something like that… the only thing that matters is what kind of person you are. There is less pressure than or the international student. For international students the story is different because they care more about them because they are a bigger financial burden on the practice so you feel much more scrutinized…. the interview air is always a little bit more stiff.”

The intensity and scrutiny in the interview is dependent on one’s residency status. The interviewer can be more critical and probing if you’re labelled ‘international’. The ‘international’ interviewee’s experience is pressurised, not just because of the need to find a sponsored position within a narrow time limit, but also because of the hostile environment in the interview setting. The widely-held conception that ‘international’ workers are a “bigger financial burden”, negatively shapes both the interview and salary negotiation process, continuing to justify lower rates of pay while in work.

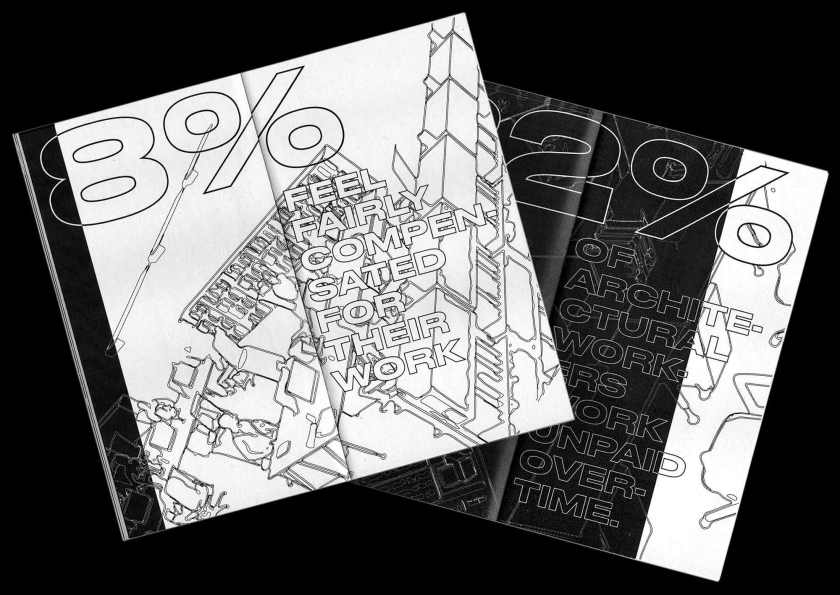

Inequality

There are huge added pressures for ‘international’ students entering into employment on top of those usually faced by recent graduates. Upon employment the pressure persists: employed with visa, workers are expected to ‘behave’ and toe the office line, while commonly subject to worse contract clauses and rates of pay. Under threat of potential deportation, there is little room to maneuver.

The treatment and experiences of workers are not equal. Those with marginalised residency status, identity, educational background and perceived ability are subject to differing realities within both architectural education and architectural practice. The process of applying for jobs, interviewing, working, all facilitate the individual and structural biases of those in positions of power.

We need to develop new modes of working and employment that allow for all people to participate and thrive within the profession.

…

…

[1] ‘Tuition Fees’, Royal College of Art <www.rca.ac.uk/studying-at-the-rca/fees-funding/tuition-fees/>

[2] ‘Sponsor a Tier 2 or 5 Worker: Guidance for Employers’, GOV.UK

[3] ‘Tier 2 (General) Visa’, GOV.UK < gov.uk/tier-2-general>

…

To search for an architectural practice that have given Visa Sponsorships previously use the link here.

Other useful links:

Citizens Advice – Immigration Advice

U.K. Council for International Student Affairs

Above:

Above: